Discovered this building while walking down Sheridan one evening, and had to come back to photograph it. It looks pretty sleek with the stainless steel fins floating above a standard brown brick facade, and I find it quite interesting that the Boys and Girls Club were willing to spend the substantial extra money on that architectural flourish. I couldn't find the architect, but it was built in 1959.

Thursday, November 26, 2009

Posted by Posted by

The Loosh

at

10:08 PM

Categories:

0

comments

Thursday, November 12, 2009

...Or, the post with a really long title :-)

This post will be added onto over time. I want to make a list of all the really cool retail spaces and storefronts in Chicago. I don't know about you, but I'm often willing to pay a little more or walk a little further in order to give money to a place that I know values, or at least spend some money on, its architecture. To get on this list, a space doesn't necessarily mean old, just unique, either in general, or if part of a chain, unique among the chain. You can kind of get a sense of what I mean by the entries on the list so far. Please comment! Need more...

The Loop

McDonald's - Wabash between Washington and Randolph

This McDonald's is unique not because it's old. It seems pretty newly-built. However, it is the most elaborate McDonald's I have ever seen. Leather seats, lacquered wood walls, and marble in the bathrooms.

Dunkin Donuts - Washington between Michigan and Wabash

This DD is cool because it has an exposed coffered ceiling in the dining room, surrounded by usual DD trim, but well lit and restored. Not often that DD spends effort on architecture.

Near North

McDonald's - Rock and Roll - Clark & Ohio

An obvious standout from the pack, this McD's is unique because of its size and the craziness put into its detailing. I mean, spider clips on a curtain wall at McD's? Also, how often can you eat a Big Mac on a Barcelona Chair?

North Side

The Green Mill - Lawrence & Broadway

With a space straight out of the 1940s, many important Chicago figures were involved in the creation and management of this famous Jazz Club, including Al Capone. It continues to be visited by celebrities often.

West Side

Margie's Candies - near Fullerton & Western, Wicker Park

Straight out of the 1960s with pieces from the 20s, this ice cream shop is yummy and architecturally unique. It is also an example of how best to get as many people as physically possible into a small space.

Near South

Eleven City Diner - 1111 S. Wabash

An awesome space. The dining room is a cavernous space, vaulted and probably 25 feet high, covered with subway tiles, topped by giant lights.

Mid-South

Uncle Johnny's Grocery - 32nd & Normal, Bridgeport

This space hasn't changed much since the 1920s. Everything from the ceiling to the freezers for the milk are original. It's also supposed to have one of the top 3 Italian Beef sandwiches in the city.

Posted by Posted by

The Loosh

at

7:40 AM

Categories:

0

comments

Sunday, November 8, 2009

As you probably know, Chicago has a Demolition Delay Ordinance that stops building that the city finds to be historically or architecturally interesting from being torn down immediately when someone takes out a demolition permit on them. There is a required waiting period, which can be up to 90 days. Since this process began in 2003, it hasn't really kept that many buildings from being torn down (that's a subject for a future post) but it has brought to light quite a few architectural interesting tidbits of the city's history for a few weeks of investigation before they bite the dust. One of the two currently under review by the city is this house, located at 4722 North Winthrop. It's been on the review list for 60 days already, so presumably the Landmarks Commission found something interesting when they did some research on it. Curious, I set out to do some research myself.

It's a nice little frame Colonial Revival house built in 1899, and you can see that it looks pretty much original with its cool little Palladian window and porch. It doesn't seem to be in the best of shape, though. The architect was Harvey L. Page. He's not that well-known of an architect in Chicago, but he actually had a pretty interesting life. Generally a classicist but a conoisseur of all styles, he began his career in Washington, D.C. When H.H. Richardson died during the construction of the last house of his career, Harvey L. Page stepped in and finished the house capably in his style. In 1890, perhaps inspired by the opportunities of a great city rebuilding from a fire all at once, he arrived in Chicago. Throughout that decade, he built houses for several of Chicago's well to. This house was one of his last, as it was built in the same year that his firm went bankrupt and he left town. About 1905, we see him in San Antonio. His work, ever a potpourri, now echoes hints of the Spanish Mission Revival and Prairie styles. In 1913, he designed the Nueces County Courthouse, considered one of his greatest works and which is now on the National Register of Historic Places. It is also apparently haunted:

Aside from the architect, the other thing that makes this house interesting is that it is a vestige of the past. Nowadays, it is located less than a block from the Lawrence Avenue Red Line station, an extremely urban location to be sure. Surrounded by large brick apartment buildings and three-flats, it feels a bit out of place. Originally, though, the property was a development by a land speculator, Lewis Cochran, that was to include mansions along the lake as part of a new streetcar suburb, not so different than Ravenswood was then or Wilmette is now. As you can see from this photo from 1897, the area was pretty rural back then.

(from Chicago ‘L’, by Greg Borzo, 2007)

So, this house sticks out because it was intended to be part of a community of mansions that never actually came to pass. When the Northwestern Elevated Company extended its line to Wilson Avenue in 1900 and to parts farther north in the 1920s, the neighborhood began to develop with densely-packed apartment buildings. In the first decade of the 1900s, it also began to develop as one of the city's premier entertainment corridors. With the Uptown Theater and the Aragon Ballroom came a deep urban vibrance. Fast-forwarding to modern times, presumably the reason the house is proposed to be demolished is either for a parking lot for the surrounding private schools or to put up a massive condo building. Neither one makes a lot of sense right now. There are already three parking lots on the block. Condos don't make a lot of sense here because the lot backs right up to a four-tracked part of 'L' that was built in the early 1920s, that runs 24 hours a day. They would be hard to market due to the noise (though, obviously, it is often done,) especially given the current state of the condo market. The only viable thing is perhaps the owners are planning a McMansion for the site. They are well within their rights to do that, but McMansions obviously don't belong in the city, and it's too close to an 'L' station to justify construction of a new single-family house in good conscience. The organization that wants to tear the house down is Apna Ghar, which is an Asian American women’s domestic abuse organization. I think the house’s current use, then, is as a shelter for battered women. There is nothing that makes it unfit for this use, aside from perhaps deceptitude, so obviously if their hope is to replace it, they should come up with a reuse plan instead.

My verdict: Architecturally, I’m not sure the case for its architectural significance is that strong, but there is some, and it’s still a cool little house and a hark back to the history of the neighborhood, AND most importantly, there’s nothing being built right now, and a vacant lot is not good for the neighborhood, especially since it is surrounded by them.

Posted by Posted by

The Loosh

at

9:53 AM

Categories:

0

comments

Friday, October 16, 2009

[Note: this was originally published on my old blog, Memoirs of a Loosh. I'm moving all the old posts here. Since 2007, the Old Colony has changed a bit, so I will publish an update to this post in short order.]

(Originally posted Feb. 24, 2008. Later edited January 12, 2009 and October 16, 2009.)

(The top photo is an early photo, from about 1895. You can tell how old it is by the absence of the 'L', which has run right next to this front entrance of the Old Colony Building since 1896. The bottom photo is from 2001.)

Chicago has a few streets that are lost in time. One of those is South Dearborn between about Jackson and Polk, especially the block between Dearborn and Congress. The same buildings stand now as they did 100+ years ago, though a little worse for the wear.

The anchor for this old block is the Old Colony Building. When it was finished in 1894, it was the tallest building in Chicago, at 212 feet and 17 floors tall. Each floor is 9700 square feet, and the total square footage is 157,406. Because its developer was from Boston and the building fronts on Plymouth Street, it was named after the “Old Colony” in Massachusetts of the same name.

The site, 84 feet long along Van Buren and 168 feet along Dearborn, was bought by Francis Bartlett in 1884, for $126,000, a price that many people at the time considered too high a price for a lot so far from the central business district of Chicago. Less than five years later, Dearborn had evolved into one of Chicago's most prestigious commercial streets and so the price was considered more than reasonable. Soon after purchasing the site, Bartlett erected a "one-story taxpayer" structure on the site, which was actually supposed to be pretty interesting architecturally, with a facade completely of glass and iron. The designer is unknown but it may have been Holabird & Roche.

Here is a picture of the site from 1892, looking southeast. The building in the foreground is the mentioned taxpayer structure. The Manhattan Building (2 buildings to the south) was just completed. The building just to the south would be torn down very soon to build the Plymouth Building, which opened in 1895 (and is currently in foreclosure as of Feb. 2008.)

The Chicago City Council was set to pass an ordinance in 1893 that would limit the height of any new structures to 130 feet. When Bartlett heard about this, he decided the time was ripe to build the larger skyscraper he knew the site could support, and which would get him a greater return on his investment. Through his connections with Bryan Lathrop, the current manager of Graceland Cemetery, Bartlett learned of the firm of Holabird & Roche. He met them and awarded them the new commission for the new skyscraper. The firm of Holabird & Roche had been founded as a very modest venture in 1881 but by the late 1880s had at least 3.5 percent of the new construction in a booming city under their design, including the three recently-completed nearby Chicago school skyscrapers: the Monadnock (1893), the Pontiac (1888), and the Caxton (1892, torn down late 1940s.)

The design was elegant. It was traditional in the sense that it included the typical tripartite arrangement of elements, with a 2-story base, a shaft, and a cornice. However, it had very little ornament, as was typical of the Chicago school, but did include lots of elements to increase rentable space and make some offices unique, such as the turrets that overhung the sidewalks, about which the architects bragged "they had achieved more than 100% site usage." The material for the base was limestone. Brick and terra cotta were used for the upper levels. The windows are all double-hung except for the middle row along the original front entrance which are chicago-style windows. An odd thing to note is that the brick that we now see as brown (see pictures at top) actually started as off-white. While all that brown is technically dirt, it is historic dirt :-) so it has been left, per the recommendation of a restoration report done in the 1970s. The following picture was submitted by Charles McLaughlin, a CAF tour guide who loves and respects the building. From this color print of the building from its early years, it can be understood how stunning the color difference is between the building's original design and its current state.

The width of the lot allowed an interior well-suited to the rule that no office be further than 26 feet from the windows in those days, when they were the main source of light, which allowed the building to be a block with no interior courtyard or light court. A central ten-foot hallway was lined with small offices, with interior walls of frosted glass and operable transoms above the doors. The floors of the hallways were yellow-brick mosaic tile, their walls were wood paneling of quarter-sawn oak.

The staircases were iron and the stairwell was originally open from ground to the top of the building. The building only has one stairwell, with emergency exit requirements handled by old-style iron fire escapes on the exterior. The elevators were originally manually-operated and were surrounded by intricate open iron grillwork. Throughout the building, much thought was put into intricate details, such as custom doorknobs that had the letters "O-C-B" branded onto them by hand.

Not including space created by enclosing various spaces since the building was built, the Old Colony has 89% rentable space, efficient even by modern standards. The basement was used for mechanical and storage space, the first floor the lobby and retail shops, floors 2-17 for offices, and the penthouse is a mechanical space. Here is the typical floor plan:

Upon opening, the building generally got positive feedback. Brickbuilder said of it in 1895, “The exterior is elegant, the interior is cramped.” In The Story of Chicago, published in 1894, just after the building's completion, it was stated “With its strong, graceful, rounded corners, its massive base, simple centre and pillared cornice, it is a delight to the eye and an ornament to the city.” In 1964, in his book The Chicago School "Not a typical example of the Chicago School. It is elegant but does not meet the doctrine that the visual divisions in the exterior represent real visual divisions in the interior, as the two-story colonnade at the top, then, has no meaning.” Like many buildings built in Chicago soon after the Great Fire, the Old Colony was built to be among the most fireproof of its day. Its features to this end included hollow tile surrounds around the structural columns and steel vaults in the suites for fireproofing, and a foot of solid masonry around exterior columns. A Russian visitor studying American fireproof construction technologies at the time, Prof. Alexander Krupsky, called the Old Colony “the most completely fire-proofed and and best constructed piece of steel work he could find in the country.”

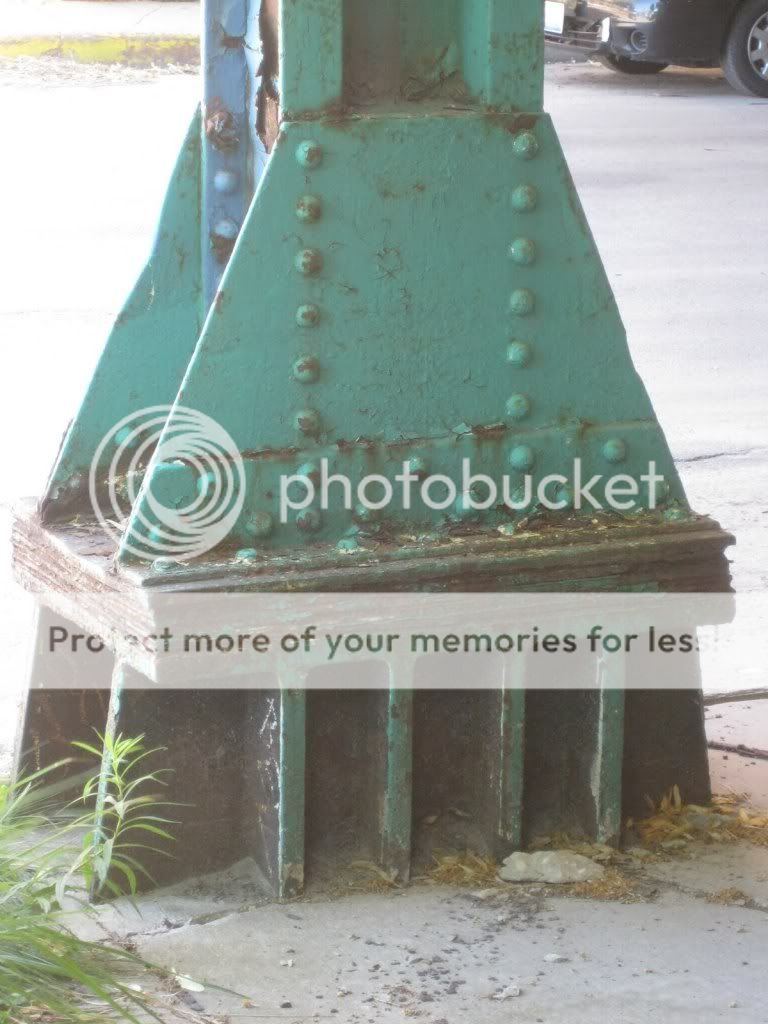

The building is a combination steel and iron structure. The beams and girders are steel, while the columns are iron Phoenix columns. Phoenix was a brand of column used mostly in bridges, manufactured exclusively by the Phoenix Iron Company, an independent steel mill in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania.

The main mill structure is still partially standing, though Phoenix steel shapes were completely phased out by about 1900.

The structural engineer for the Old Colony Building was Corydon T. Purdy. Because a skyscraper had not been built to such a height before, a solution had not been found to deal with the huge wind forces that would buffet such a large building. The Old Colony was the first use of portal wind bracing. This consisted of four arches per floor. This resulted in no lost rentable space, and can only be noticed be tenants in the form of a few arched passages between rooms. The technology was successful, as it was tested soon after the building was completed, and with a 70 to 80 mile per hour wind, the building was off plumb only three sixteenths of an inch.

Some interesting structural details:

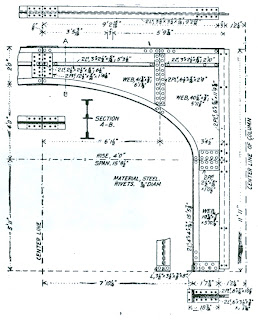

Beam to column connections:

Details of how steel was used to frame the overhanging turrets.

The foundation for the building is a system known as the raft grillage. It was first developed by John Root for the Rookery in 1888. It consists of a grid of steel beams embedded in concrete. The foundation of the neighboring six-story building went over the Old Colony's lot line and no agreement for a party foundation could be made. The architects got a signed agreement, however, that the old building's foundation could handle the weight of the Old Colony's southernmost column line. By the time construction had reached the third floor of the Old Colony, however, the old building's foundation had settled nine inches, so apparently the old foundation could not handle it. A new method had to be devised. Corydon T. Purdy developed a cantilever foundation, in which the foundation ends before the southernmost column line. Overall, the deferential settlement ended up being only one inch between the north and south ends of the building.

Foundation Plan

Section of Cantilever foundation

One of the most interesting aspects of the Old Colony Building in modern times is the fact that many of its mechanical systems are original, over 100 years later. Part of this is because its plumbing is all done via “wet” columns, meaning the pipes are embedded in the structural system, which makes them nearly impossible to fix or upgrade. Water is provided to the building gravity-fed via two original oak water tanks. The main one has a capacity of 1600 gallons, operates on a float system, and provides water to the lower 16 floors. A much smaller oak tank is higher, above the roof, and is fed from the lower tank, via a pump. It serves exclusively the seventeenth floor, because the pressure from the lower tank is not high enough to serve plumbing fixtures on that floor, crucial in the early days since the only men's bathroom was on that floor, in a massive skylit room. Because women were rare in office buildings in the late 19th century, a smaller restroom was provided for them on the 8th floor. By the 1970s, one had been added to the 17th floor as well. In addition to the main restrooms, a small closet off the stairwell landing including a urinal for use of building tenants. Each office originally had a closet that included a sink.

The building's heating system has been upgraded. The building is currently heated through three low-pressure steam boilers that were added in the 1990s. Until then, heating had been done by one high-pressure natural gas boiler and one coal boiler, though the coal boiler was out-of-service by the late 1970s. When it had been in operation, coal was delivered through a trap door in the sidewalk that led to a storage room in the basement. Steam is sent to the top of the building and gravity-fed down to radiators on each floor. The radiators were originally cast iron, and many of them remain. Heat flow to each tenant unit is controlled by manual valves on the radiators. There is no central air conditioning system. The roof cannot support the weight of a cooling tower, so cooling is done by individual smaller systems. The ventilation remains the operational transoms above the doors to each office.

This picture shows an unusual custom radiator that was built to curve around a structural column. (Left) One of the old boilers (Right.) The intervening years have held a variety of interesting challenges for the Old Colony Building. In the late 1940s, the Dearborn Street Subway (now the Blue Line) was constructed. To keep the building from settling as a result, caissons were added under the western side of the building. The Congress Parkway was built about 1950 just three buildings south of the Old Colony. This signalled the demolition of several old highrises in the vicinity, greatly altered the cityscape in the which the Old Colony sat and the blocks it inhabited, and because of the anti-pedestrian nature of the new highway, signalled the beginning of a decline of pedestrian traffic in the area, bad for a building with many first floor retail shops. However, these shops have generally remained leases, though the quality of tenants has varied. By the 1960s, the south end of downtown had become a forlorn, forgotten area, so attracting tenants was difficult. This remained true through the 1980s. In 1968, a restaurant exploded across Plymouth Court from the Old Colony's east entrance, so that entrance had to be rebuilt, and was done so in a modern style. At some point, the north – originally main – entrance was enclosed to provide more rentable space on the first floor and a storage area on the second. The elevators have also been replaced by modern automatic models. The freight elevator remains manually operated. These renderings show the difference between the originally north entrance and the enclosed one.

Despite these changes, some of the original flourishes reportedly remain intact behind the walls. The original ornamental elevator grillwork was never removed, just encased. The original coffered ceiling above the north entrance remains in the second floor storage space.

In the report written in the 1970s about the building (see references below), it was reported that some key pieces of the original fabric remained. Some of the yellow brick mosaic floors apparently remained in one hallway, much of the original woodwork, and the urinal closets remained intact. The building had received National Register status in 1976 and Chicago Landmark status in 1978. 30 years later, in October 2007, I went to see how much of that fabric remained. The area around it, however, has improved greatly since the 80s, and in some ways the building has been a victim of its own success as of late. Some floors are very well-appointed, some not, but none have much of the original intact. The urinal closets, may however, be. They were all locked upon my visit.

The old woodwork remains intact in many places, or is replaced quite faithfully. (Upper Right picture.) It's funny how this unit modification exposed the US Mail chute that runs through the building. A mail chute runs through most old buildings in Chicago (Bottom picture. Here's the door to the urinal closet on each stairwell.

The old iron staircase remains intact and open. (Left) Not sure what these transoms were for. Getting light and air into the stairwell, maybe? (Right)

What will happen to the Old Colony? Well, hopefully, someone comes around and restores the lobby to its old beauty. That could add a lot to the building's historic charm. Currently, a rather drab single-story modern lobby greets visitors. In general, it continues to do a good job of serving as an office building, mostly for lawyers and the occasional architect. I hope no one decides it's time to turn it into condos. This one still has many years to go before it can be written off by the business community. Its combination of historic statuses should keep it from getting maimed too badly or torn down for the foreseeable future, at least we can hope.

(All information in this post is my original research. I post it because you might fight it interesting. Don't steal it!!):

Where I got my information:

Birkmire, William H. Skeleton Construction in Buildings. 2nd ed. New York: J Wiley, 1894., 183-205.

Bruegmann, Robert. The Architects and the City: Holabird & Roche of Chicago, 1880-1918. Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 1997.

Bruegmann, Robert. Holabird & Roche & Holabird & Root: An Illustrated Catalogue of Works, 1880-1940. New York: Garland, 1991.

The Chief Engineer. “The Old Colony Building: If These Walls Could Talk…” http://www.chiefengineer.org/article.cfm?seqnum1=525 .

Commission on Chicago Historical and Architectural Landmarks. Old Colony Building. Chicago: Commission on Chicago Landmarks, 1977.

Condit, Carl. Chicago School of Architecture: A History of Commercial and Public Building in the Chicago Area, 1875-1925. Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 1964.

Historical American Buildings Survey. “Old Colony Building.” Published 1964. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.il0046 .

Historical Society of the Phoenixville Area. “Phoenix Iron and Steel: The Iron Works – Early Years.” http://www.phxsg.org/hspa/iron_works.html .

Kirkland, Joseph. The Story of Chicago, Vol. II. Chicago: Dibble Publishing Co., 1894.

Weese, Harry and Associates. Four Landmark Buildings in Chicago’s Loop: A Study of Historic Conservation Options. Washington: US Govt. Printing Office, 1978.

Posted by Posted by

The Loosh

at

9:29 PM

Categories:

0

comments

If it's 80 years old, is it still considered retro? Perhaps there's a different word for it. In any case, this Sears store is very old. It is the oldest continously-operating Sears store in the United States, tied with a store on the south side of Chicago on 79th Street (I will get down there to photograph it some day.) Both stores were built in the mid-1920s and both opened on the same day, November 1, 1925. Before that, there was only one Sears store, the very first, at Homan Ave. & Arthington, on the original Sears corporate campus on the west side. That store closed long ago and the campus has been mostly demolished. However, its old power house was renovated to become a new charter school, Power House High, this year.

Originally, as it is today, this store was surrounded by houses and urban streets, so it's now one of the smallest in the system. But, since Sears has never put out the money to fully renovate or replace it, it remains a cornerstone of the neighborhood, deeply embedded within it. Sadly, the enormous windows through which light once streamed abundantly into the massive warehouse-like space have been boarded up, and with vinyl siding no less, and the cornice has been removed (actually, it's hard to tell if there ever was one - look closely at the old picture - but something has been removed or massively changed at the top of the walls.) The only (most likely) original features remaining on the exterior are the fire escapes and the mosaic tile patterns in shades of brown featuring the old Sears & Roebuck Co. logo. It is a compliment to Sears that they have avoided covering the exterior with too much unnecessary modern signage - only one new Sears logo hangs near the front door. Yet, despite its physical devaluation over time, it's hard not to imagine this building's former beauty.

The interior is much like the exterior, once probably beautiful, nowadays far less so. I don't have pictures of it yet because employees were everywhere the last time I was there, and I prefer to ask forgiveness rather than permission. However, some original features are intact, including a beige escalator that is definitely old, though perhaps not original to the building. Because of the closely-spaced interior columns, the retail areas tend to be carved up in odd ways, and the store restaurant/coffee shop is located on a strange low-ceilinged third floor added later as a loft above part of the second floor. Again, though, it is possible to imagine the awesomeness of the space with light shining through the massive windows lighting up brand new appliances eyed by people seeking to spend their newfound wealth accumulated in the roaring 20s.

Posted by Posted by

The Loosh

at

2:17 PM

Categories:

0

comments

Sunday, August 23, 2009

The seen:

The Unseen:

Location: Just east of the intersection of Chicago and Milwaukee on Ogden, in West Town.

Posted by Posted by

The Loosh

at

3:38 PM

Categories:

0

comments